The Great O’s

TL, DR: The Second Coming is now.

by Lucy Tucker Yates

The prayers of the O Antiphons, the Great Antiphons of Advent, are the most urgent, elegant condensation of humanness I know of. As in the circular breathing of an oboist, the words on our lips give life to generations past. They focus centuries of adoration, impatience, woundedness like a spotlight. They are the poetry I would send out into space.

TL, DR: The Second Coming is now.

by Lucy Tucker Yates

Photo: Mariadonata Villa

There is a song by Charles Ives (Memories I) that goes, "Weee're SIT-ting in the op-'ra house, the op'-ra house, the op'-ra house, We're WAIT-ing for the cur-tain to arise With won-ders for our eyes... A FEEL-ing of expec-tancy, A CER-tain kind of ec-stasy, Expectancy and ecstasy--Expectancy and ecstasy---SHHHHHHSSSSS!!!"

Such FEEL-ings surround and bind us together during Advent: we huddle in the grand theatre of heaven-and-earth, eager to see our hero revealed, ready for our leading man to light the shadows, right the wrongs, mete justice. The gaze of all is upon the stage.

The prayers of the O Antiphons, the Great Antiphons of Advent, are the most urgent, elegant condensation of humanness I know of. As in the circular breathing of an oboist, the words on our lips give life to generations past. They focus centuries of adoration, impatience, woundedness like a spotlight. They are the poetry I would send out into space.

How is such poetry fashioned? “Antiphon” comes from Greek ἀντίφωνον, “opposite voice,” and Socrates of Constantinople writes that Ignatius of Antioch (the third down from Saint Peter himself) introduced antiphony into worship after having a vision of two choirs of angels. Antiphons are often lifted from the Psalms or prophecies and designed for call and response, and to be sung as refrains.

So imagine everyone in the world, together, with the house lights dimmed, with or without ushers, with or without tickets, singing "O come, o come, Emmanuel." Remember how the hymn works: the first half of each verse invokes a Messianic title and attribute of Jesus, and the second half makes a request, drawing on His strength, from our weakness. "And ransom captive I-i-is-ra-el." Notice that the hymn is a beautiful and durable recasting (in the Aeolian mode), but know now that in the ancient Italian antiphons (the first, “O Sapientia,” appears in Boethius in the sixth century) the body–of prayer, of poetry, of past, of future–is suspended between the "O" and the "come".

Each verse calls on the Most High, offering a quality, a role, a memory, as a fan might smile up at the star: "Remember when you were the commander in that crazy long battle? You shredded that day. Can you come down and shred here?" Some petitions sound well-bred and -schooled: "come, and teach us the way of prudence." Some seem brisk, but really anxious: "don’t be slow, already!" All are predicated on His coming.

And the call is always the same–a great round vocative. "Vocative" comes from Latin “vox,” voice, and one of the glories of the human voice is the shape of O. Drop your jaw and try one. You may find that the air can't decide whether to rush out hot, as in relief or in pain, or to swoop in cold, as in shock or in awe, or to park and pop open the vocal folds, as in recognition. You are suspended in a tunnel, or a cave, or a cathedral, or a cheekily perfect dewdrop. A mouth like a portal. Round as a belly. Curved as Time.

Because God is master of inversion–we know the plot of our Trinitarian play works upside down, backwards, and inside out–the lines allow a neatly flipped acrostic mnemonic. Here are the names from end to beginning, from 23 to 17 December:

Emmanuel (God-with-us, the peoples' desire, giver of laws)

Rex Gentium (King of the Peoples, who made humankind from earth)

Oriens (Rising Star, Sun of justice)

Clavis David (Key of David, opener of locks, shutter of mouths)

Radix Jesse (Root of Jesse, life abiding in the tree that was cut down)

Adonai (Lord, Ruler over nature and the House of Israel)

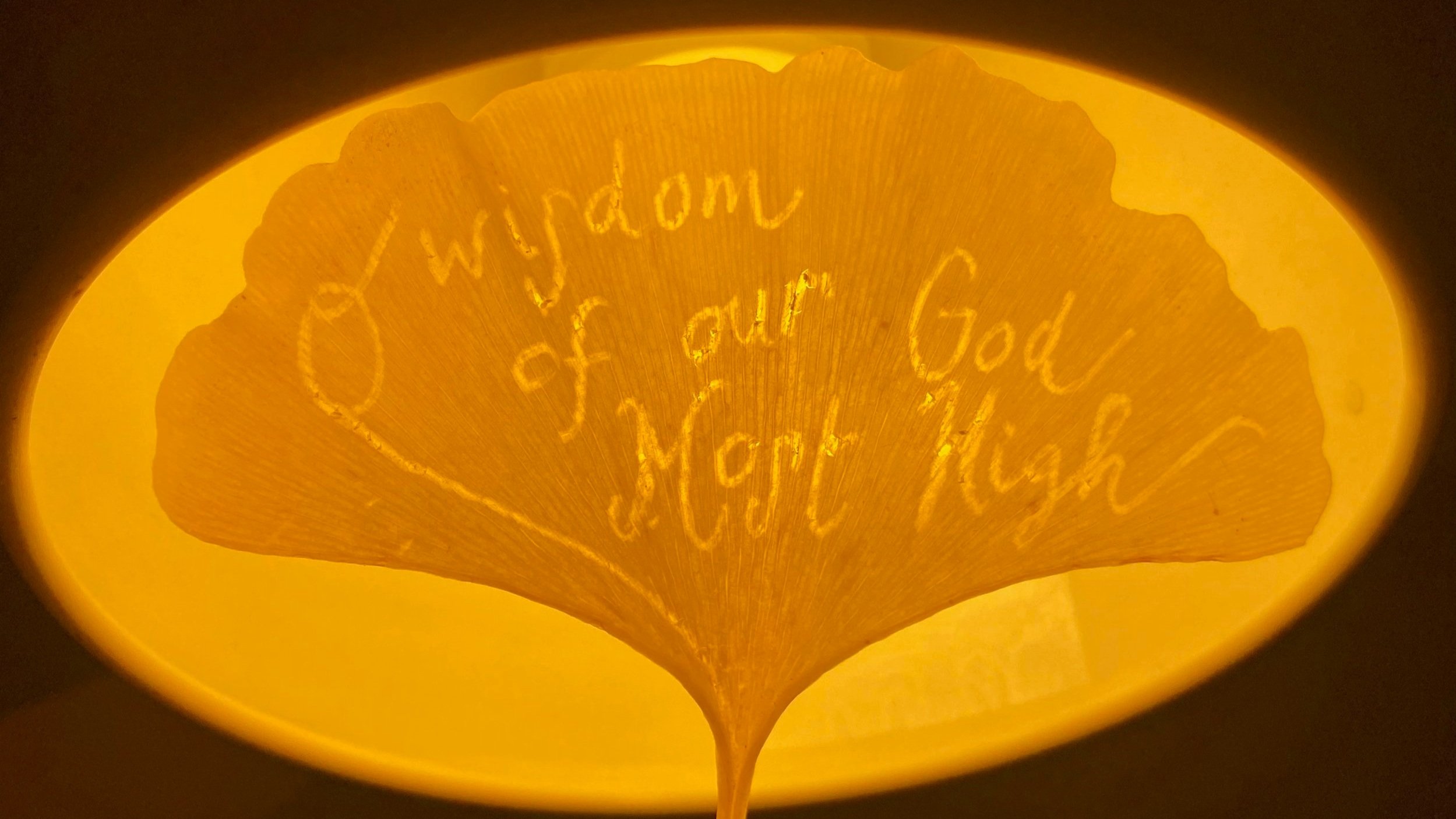

Sapientia (Wisdom, the creating Logos and incarnate Word)

From the Parousia back to the creation. "Ero": "I will be [there]"; "cras": "tomorrow." The answer is within the questions: He is coming! He is the other “choir” in our antiphon! The secret voice, the wider circle! But when is "tomorrow"? Might verb tenses not work back and forth, too–or around and around? What if He is already here? What if we are all in the play?

We are presenting the antiphons in their traditional setting, framing the Magnificat, so as to hear the expectations of the leading Man amid the satisfactions of the expectant leading Lady. We are singing solos, but we represent the whole Church, who plays not only the part of the Prophets but that of the Mother of God.

When singing of the First Coming we always invoke the Second: when yearning for the Second we always echo the First. Try the O again, and this time raise your eyebrows and open the top half of your face. Lift your cheekbones and twinkle your eyes. There, don’t you feel like a child who’s discovered a secret? OHHHHH!! That’s the kind of O we don’t often see, because its wearer claps their hands in front of it to avoid giving too much away. Inside its arena, the Parousia is all one. Emanuel, God (already) with us.

And is this not the fullness-of-time itself? To seek to usher in on earth that which we ask the Redeemer to grant from Heaven? To meld the memory of Alpha and the desire of Omega? May we always be rounded to call and willing for His response: I will be there. I Am. Here. Now. May we always be caught between the expectancy of "Come" and the ecstasy of "O."

_________________________

O Sapientia, quae ex ore Altissimi prodiisti,

attingens a fine usque ad finem,

fortiter suaviterque disponens omnia:

veni

ad docendum nos viam prudentiae.

O Wisdom,

which came out of the mouth of the Most High,

and reaches from one end to another,

mightily and sweetly ordering all things:

come,

and teach us the way of prudence.

O Adonai, et Dux domus Israel,

qui Moysi in igne flammae rubi apparuisti,

et ei in Sina legem dedisti:

veni

ad redimendum nos in brachio extento.

O Adonai,

and leader of the house of Israel,

who appeared in the bush to Moses in a flame of fire,

and gave him the law on Sinai:

come

and redeem us with an outstretched arm.

O radix Jesse, qui stas in signum populorum,

super quem continebunt reges os suum,

quem Gentes deprecabuntur:

veni

ad liberandum nos, jam noli tardare.

O Root of Jesse,

which stands for an ensign of the people,

at whom kings shall shut their mouths,

and whom the Gentiles shall seek:

come

and deliver us, and tarry not.

O Clavis David, et sceptrum domus Israel;

qui aperis, et nemo claudit;

claudis, et nemo aperit:

veni,

et educ vinctum de domo carceris,

sedentem in tenebris, et umbra mortis.

O Key of David,

and Scepter of the House of Israel,

who opens and no one can shut,

who shuts and no one can open:

come,

and bring the prisoners out of the prison-house,

them that sit in darkness and the shadow of death.

O Oriens,

splendor lucis aeternae, et sol justitiae:

veni,

et illumina sedentes in tenebris, et umbra mortis.

O Day-spring,

brightness of the light everlasting,

and Sun of righteousness:

come

and enlighten them that sit in darkness and the shadow of death.

O Rex Gentium, et desideratus earum,

lapisque angularis, qui facis utraque unum:

veni,

et salva hominem,

quem de limo formasti.

O King of nations and their desire;

the Cornerstone, who makes them both one:

come

and save mankind, whom you formed of clay.

O Emmanuel, Rex et legifer noster,

exspectatio Gentium, et Salvator earum:

veni

ad salvandum nos, Domine, Deus noster.

O Emmanuel, our King and Lawgiver,

the desire of all nations and their salvation:

come

and save us, O Lord our God.

You Won’t Miss the Burgers

Annunciation (detail), by Matthias Stom

by Suzanne M. Lewis

In 2017, I noticed a sore on my tongue.

By Sunday, October 1, 2017 (the feast of St Thérèse, my Confirmation namesake and special friend), my oral pain was intense as I had the joyful task of thanking each of our speakers and volunteers for their rich contributions and gifts of self throughout that beautiful long weekend at Pittsburgh’s St. Paul Cathedral, where we’d just held our 6th annual Festival of Friendship. I didn’t suspect, then, that two weeks later, on October 15 (Teresa of Avila’s feast), I would call my husband from outside an oncologist’s office to say the three-word sentence that no one wants to speak or hear: “I have cancer.”

In the waiting room before one of my chemo infusions, I met a woman wearing a wide apron, in which she carried her own IV bag that provided a slow drip and allowed her to live at home while receiving treatment. She had arrived for her periodic changing of the bag, and began to explain to me how the medicine she was receiving had changed the flavors of food: “A hamburger just isn’t a hamburger anymore, you know? It tastes funny, like. And forget nachos! I can’t enjoy the taste of my favorite meals. I tell you, if the cancer comes back after this, I’m going to refuse treatment. I’d rather die than live like this.”

This past year, on October 1st, it felt particularly gratifying to kick off the month-long online 2020 Festival of Friendship by offering a panel discussion honoring St. Thérèse and St. Teresa, as well as Edith Stein and Mother Teresa, four “boss” saints who have had such an enormous impact on the world. Only two weeks earlier, my cancer doctors at Cleveland Clinic had pronounced that marvelous and golden word: remission. I knew these four women were at least partly responsible for my healing.

But I’ve also wondered about that woman, whose life meant so little to her that she would trade it for the taste of a Big Mac. Meanwhile, throughout this year, our society’s many failures to respond generously to the exigencies of the pandemic have uncovered a different sort of cancer: despite our stated belief in the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” there are numerous signs that the particular human lives of our fellow citizens do not matter to many of us. This year’s Festival of Friendship addressed this problem from multiple angles, including a focus on the inestimable value of elderly persons; ethical concerns arising from the pandemic; restorative justice in Brazil; and music produced by Black female composers, poets, and vocal artists. These events each revealed a common root cause for the evident disinterest in the lives and well-being of our fellow citizens: a fundamental apathy toward one’s own, unique, God-given life.

At some point, in the experience of each and every authentically religious person, a luminous question arises. This question carries with it all the wonder, all the longing, and all the curious hope expressed in Mary’s query to the angel, “How can this be?” (Lk 1:34). The same astonishment reverberates in Elizabeth’s amazed exclamation, “Who am I that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” (Lk 1:43).

Who am I that You are mindful of me? (cf. Ps 8:4). If you have never asked God some version of this question, then you’ve also never allowed Christ’s own question – Are not all the hairs of your head counted? (cf. Lk 12: 6-7) – to sink down into the roots of your being and startle you out of your petty worldliness. You may engage in all sorts of religious practices, but you haven’t yet embarked on the adventure of a truly religious life. Only after you’ve made a habit of viewing yourself with the esteem God has for you, can you turn your gaze to others and recognize that the Lord cherishes each human life as fiercely and as wholly and as astonishingly as he loves you. Without this intuition, you cannot fulfill Christ’s commandment to love one another as he has loved you.

When you – one lone person – begin to ask this question (“Who am I that You are mindful of me?”), your life becomes something new, something exceptional. Christ refers to this as an “abundant life” (cf. Jn 10:10) or as “the hundredfold here below” (cf. Mt 19:29). With this hundredfold, you develop an endurance you can’t explain and discover a patience you could not produce through force of will. Your creativity grows as you see an increase in your desire to address the predicaments and wounds of others. Soon, another person, unbidden, joins with you. One by one, others see and are magnetically attracted to the two of you. Together you will each roll up your sleeves and take the small, possible steps indicated by the boundless esteem for life you share. You will “start by doing what's necessary, then do what's possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible” (St. Francis of Assisi). Believe me, you will not miss the hamburgers when this happens.

Welcome to your one wild and precious life.

Your One Wild and Precious Life: End of Year Campaign

We are full of wonder and gratitude to announce that, due to the generosity of our most committed donors, we have already received over $8,000 in gifts, which bring us more than halfway to our end of year campaign goal of $14,000. We need you to join us in building a culture of dialogue and healing in the public sphere. Your contribution makes you a standard-bearer in the cause to build a culture of encounter and mutual respect.

Our theme for Festival of Friendship 2021

Photo courtesy of: Sister Thea Bowman Cause for Canonization

by Suzanne M. Lewis

We are full of wonder and gratitude to announce that, due to the generosity of our most committed donors, we have already received over $8,000 in gifts; this brings us more than halfway to our end of year campaign goal of $14,000. We need you to join us in fostering dialogue and healing in the public sphere. Your contribution makes you a standard-bearer in the cause to build a culture of encounter and mutual respect.

We have found that the best tools for fostering true dialogue and effecting real healing within our broken culture are humanities education and free cultural events.

Humanities Education

Despite an overall increase of 29% in bachelor’s degrees awarded over the ten-year period ending in 2016, the steady decline in the number of humanities degrees conferred has only accelerated. In 1967, 17.2% of all degrees conferred were in the humanities. By 2014, that figure was down to 6.1%. Why should this precipitous drop concern us?

The very name “humanities” provides the answer: the various subjects that make up the humanities provide a curriculum for becoming more human. The more we lose touch with the humanities, the more we lose access to certain dimensions of our own humanity.

“Where scientific observation addresses all phenomena existing in the real world, scientific experimentation addresses all possible real worlds, and scientific theory addresses all conceivable real worlds, the humanities encompass all three of these levels and one more, the infinity of all [imaginable] worlds.” ― biologist, Edward O. Wilson

The humanities teach us how to extract and absorb facts from a document, how to interpret data, particularly in relation to the whole field of knowledge, and how to evaluate whether a claim is true or false; they also show us how to formulate an argument and find evidence to support our own claims; most importantly, they put us in conversation with others who grapple with the same human questions that preoccupy us, expose us to other perspectives, and open us to continuous learning – even teaching us how to learn from those with whom we disagree.

A quick visit to a handful of social media platforms, or a cursory scan of the headlines for competing news outlets, provides overwhelming evidence of how the tragic decrease in humanities education has had devastating effects on our public discourse.

“Depth of understanding involves something which is more than merely a matter of deconstructive alertness; it involves a measure of interpretative charity and at least the beginnings of a wide responsiveness.” ― English literature scholar, Stefan Collini

With these considerations in mind, Revolution of Tenderness has founded Convivium: A Journal of Arts, Culture, and Testimony, Convivium Press, and the Festival of Friendship. Each of these initiatives provides educational tools and programming to introduce humanities education into the public sphere. We sell our journal, and all other educational resources, at cost so that they may be accessible to the greatest number of people. Our free cultural programming offers content from pre-eminent scholars and experts while modeling the practice of respectful dialogue.

Free Cultural Events

The annual Festival of Friendship, our largest free and open cultural event, contributes a celebratory dimension to our educational work. This year, though we had to move the Festival online, we had nearly 1,300 attendees, a new record for us!

While our printed texts, videos, and other materials provide crucial substance, our events confer a body with living, human features. Without this living body, learning becomes a dry and toilsome duty, a “prize” to capture and use, or a meaningless intellectual exercise. Instead, our free events serve as life-giving feasts for the human heart and mind.

Our next exciting project will involve a commission for a new piece of music from composer Richard Danielpour, who spoke at the Festival of Friendship last month. The projected performance will take place in early 2021. We’ll provide further details as they become available.

Our working hypothesis, that “all things cry out in unison for one thing: Love” (13th Century friar and poet, Jacopone da Todi), allows us to “assume an extended shared world” (Stefan Collini) and meet anyone and everyone with curiosity and an embrace. Our festive gatherings serve as laboratories, where speakers and performers present their findings and launch new experiments in human flourishing.

Your generous support for Revolution of Tenderness makes you a creative protagonist who generates a culture of dialogue in the public arena. Please contribute to our end of year campaign today. Revolution of Tenderness is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. All donations are tax-deductible.

Your One Wild and Precious Life

Join us on this adventure. Share your ideas, your help, your ardent prayers, your particular talents, your resources, and your energy as together we prepare our 9th annual Festival of Friendship. Your one wild and precious life cannot be substituted or duplicated.

Photo courtesy of: Sister Thea Bowman Cause for Canonization

We are overjoyed to announce the theme for Festival of Friendship 2021: Your One Wild and Precious Life.

You meet certain people along the path of life: people who seem more alive, more human, more original. They stop you in your tracks. They make you ask yourself: What is the secret to their fascination? How did they find their intensity? Where can I pick some of that up for myself?

Sister Thea Bowman is one of those people. Next year, we’ll examine her life for clues to the source of her ardor and joy. If we want to fully inhabit our lives as Sister Thea did, we need the courage to stop wasting our own time, and to mean something luminous, grand, wild, exceptional, and precious when we use the word “I.”

Join us on this adventure. Share your ideas, your help, your prayers, your particular talents, your resources, and your energy as together we prepare our 9th annual Festival of Friendship. Your one wild and precious life cannot be substituted or duplicated. St. Catherine of Sienna wrote, be who you were meant to be, and you will set the world on fire. Let’s create a conflagration together!

Contact me at suzanne [@] revolutionoftenderness [dot] net in order to join the Revolution of Tenderness!

A Free Abundance of Great Things at the Rimini Meeting

The heart, unimpeded by calculation and not distracted by the dream of personal gain, can and does open out toward whatever is true, and beautiful, and just. The Meeting is the fruit of this discovery and its consequence: an embrace for every aspect of reality, because all is a gift, all has been given by Another.

Disabled Turnstiles at the Rimini Meeting

by Suzanne M. Lewis

This article first appear on ilsussidiario.net, in 2010

Entry into the enormous conference center, where the Meeting for the Friendship Among Peoples is held, is free. Indeed, for each of the past 31 years that this extraordinary cultural festival has been held at the Italian seaside resort town of Rimini, entrance to the exhibits and talks has been free.We often think of “free entry” in negative terms: there is no charge, one does not pay; however, the gratuitousness of the Meeting in Rimini does not represent a lack, but rather a fullness.

Immediately upon arriving at the Fiera of Rimini, one can see that the turnstiles, with their rotating metal arms, have been disabled; the metal spokes all hang down to allow free passage into the gigantic space that is completely filled: with fascinating exhibits and lectures given in halls filled to capacity, with concerts and dramatic readings and theater performances and film presentations, with sporting events, with shops, with signs, with restaurants, and with thousands of people (800,000 visitors and 40,000 volunteers during the week-long annual event).

Each year the Meeting has a theme around which the exhibits and talks are built. This year’s theme was, “That nature which pushes us to desire great things is the heart,” and at the Meeting, there were eight large exhibits: 1) “A Use for Everyone. Each to His Work. Within the Crisis, Beyond the Crisis,” concerning the recent ongoing economic crisis; 2) “From One to Infinity. At the Heart of Mathematics,” created by the Euresis Association, an international group of scientists that has created many stunning exhibits for the Meeting in past years; 3) “Flannery O’Connor. A Limit with Infinite Measure,” concerning the life and work of the great 20th Century American author; 4) “At the End of the Road Someone Is Waiting For You. The Splendor of Hope in the Portico of Glory,” an art historical meditation on the beautiful arch at the pilgrimage destination of Compostela, in Spain; 5) “Stephen of Hungary. Founder of the State and Apostle to the Nations;” 6) “‘But I Put Forth on the High Seas’. Ulysses: When Dante Sang of the Stature of Man,” concerning a passage from Dante’s “Inferno”; 7) “A Heaven on Earth. The Samba of the Hill,” about the birth of the Brazilian samba music in the favelas; and 8) “Gdansk 1980. Solidarity,” tracing the events that led to Polish independence from the Soviet Union.

If the Meeting in Rimini were only to include these eight exhibits, it would be a great cultural event; but in addition to these larger exhibits, there were many smaller exhibits, presenting various diverse subjects including: the frescoes within the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, Italy; education as something belonging to the human heart; the life of St. Gianna Beretta Molla; the relationship between love and literature; the work of particular missionaries in Africa; the Russian pianist Marija Judina and her relationship to Stalin; and more.

Each of these exhibits, large and small, was created by groups of individuals with an intense passion for their subject matter and a desire to communicate their fascination to others. Many of the curators provide guided tours within the exhibits. They also train additional volunteers to give guided tours that are then offered in many different languages. It is incredible that passion is the only reason for the huge expenditure of time and work that each exhibit requires; no one receives a financial gain from mounting these exhibits and there is no governing body that awards prizes to the best exhibit; thus neither money, nor glory, nor professional advancement, nor even a spirit of competition is involved in the decision to begin work on an exhibit or in seeing the project through to completion. In fact, there is no evaluation process (questionnaires, exit interviews, etc.) in order to provide market analysis or to assure attendance at future Meetings.

And the curators and guides are not the only people with a passionate interest in the subject explored in any given exhibit. Close observation of the thousands of visitors who file through the exhibits reveals faces in deep concentration, hungry to soak in every detail, whether communicated by the guides or present on the many panels covered in texts and images. All this effort and work is, moreover, for something that most people consider ephemeral and unnecessary for daily survival: cultural study.

This passion alone holds the key to the meaning of the Meeting. It generates the exhibits and also finds expression in the many talks and panel discussions offered in several large lecture halls simultaneously throughout each day of the Meeting. Often there is not enough room in auditoriums that hold thousands of people and the crowds spill outside the doors, onto the floor in order to watch the proceedings on large video screens. Imagine a talk about mathematics by a professor from Princeton University (and no one’s grade depends on it), where hundreds of people cannot fit into the lecture hall and must sit on the floor, watching on a screen! These discussions and talks are given by exhibit curators and experts in many fields. Among the many speakers at the Meeting in Rimini this year were Rose Busingye, a nurse and the Coordinator of Meeting Point of Kampala, a center for Ugandans with AIDS; Mary McAleese, the President of Ireland; Gerhard Ludwig Müller, Bishop of Ratisbona; Miguel Diaz, the US Ambassador to the Vatican; Joshua Dubois, Director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnership; Diarmuid Martin, Archbiship of Dublin and Primate of Ireland; John Milbank, Lecturer in Religion, Politics and Ethics at Nottingham University; Edward Nelson, Lecturer in Mathematics at Princeton University; Mario Livio, Senior Astrophysicist at the Hubble Space Telescope Science Institute; William McGurn, Journalist with the Wall Street Journal; Chen-Hsin Wang, Lecturer in German Language in the Departments of Music and Psychology at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taipei, Taiwan; Angelo Scola, Patriarch of Venice; Angelino Alfano, Italian Minister of Justice; David Maurice Frank, Native American from the Ahousat Reserve, Vancouver Island, Canada; Aliyu Idi Hong, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Nigeria; Shah Mehmood Quereshi, Minister of Foreigners for the Islamic Republic of Pakistan; Shōdō Habukawa, Buddhist Monk and Lecturer at Koyasan University; Tareq Oubrou, Rector of the Mosque of Bordeaux; Joseph H. H. Weiler, Director of the Straus Institute for the Advanced Study of Law and Justice and Co-Director of the Tikvah Centre for Law & Jewish Civilization at the New York University; and many leaders in Italian government and business — to name only a few!How is it that so many professionals from diverse fields find the passion to offer their work as a free gift to anyone who approaches? And what is it that draws these crowds, year after year, to a fascinated engagement with the cultural exhibits and lectures at the Meeting? Where does this passion come from? The theme of the 2010 Meeting offers a clue: the human heart. The heart, unimpeded by calculation and not distracted by the dream of personal gain, can and does open out toward whatever is true, and beautiful, and just. The Meeting is the fruit of this discovery and its consequence: an embrace for every aspect of reality, because all is a gift, all has been given by Another.

The Festival of Friendship as a Courtyard of the Gentiles

“The Courtyard of the Gentiles calls for the sharing of a common thirst in a universal, comprehensive, catholic perspective: the opening to each other as [what gives] dynamism to human life.” He called for, “respectful encounters, in sincere dialogue and in a passionate search.”

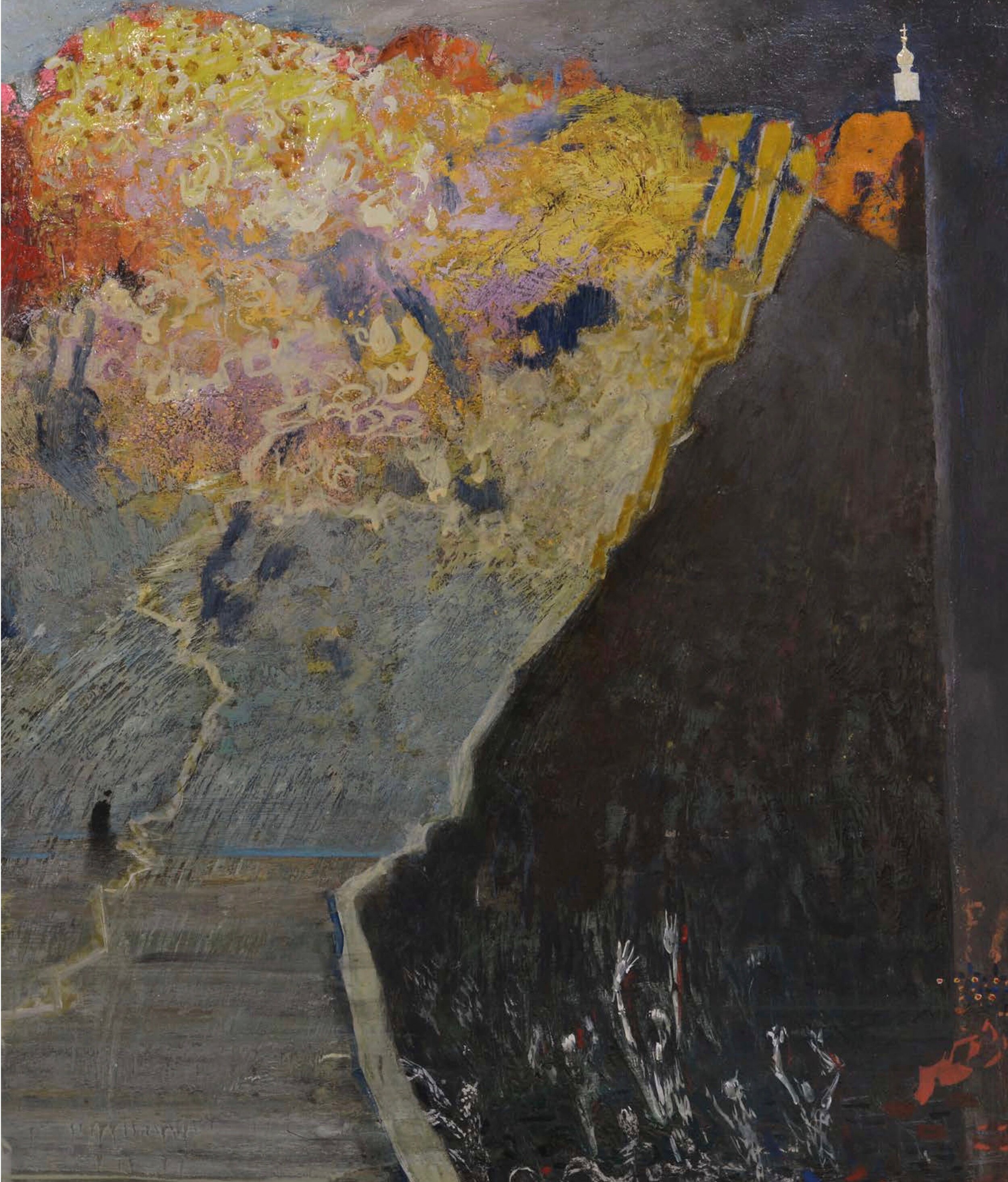

Road to the Temple, by Victor Zaretsky

In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced a new project, very dear to his heart, called the “Courtyard of the Gentiles.” His desire was to open a space for dialogue among peoples of different faiths or no faith. He described the modern world as "a windowless building of cement, in which man controls the temperature and the light; and yet, even in a self-constructed world, we draw upon the 'resources' of God, which we then transform into our own products. What can we say then? It is necessary to reopen the windows, to see again the vastness of the world, of heaven and earth, and to learn to use all things in a good way." This statement expresses our own vision at Revolution of Tenderness. Taking St. Paul's motto, "Test everything; keep what is good" as our own, we seek to reopen the windows Pope Benedict spoke of. Now, more than ever before, this is an urgent undertaking.

Pope Benedict XVI took, as his inspiration for the initiative, the name for the open air atrium at the Temple of Jerusalem, “a space in which everyone could enter, Jews and non-Jews, …[to engage] in a respectful and compassionate exchange. This was the Court of the Gentiles… a space that everyone could traverse and could remain in, regardless of culture, language or religious profession. It was a place of meeting and of diversity.” Our various initiatives, especially the Festival of Friendship, seek to provide similar spaces where “respectful and compassionate exchange” can happen.

Pope Benedict reminded us that Jesus said, “The Temple must be a house of prayer for all the nations (Mk 11: 17). Jesus was thinking of the ‘Court of the Gentiles,’ which he cleared of extraneous affairs so that it could be a free space for the Gentiles who wished to pray there to the one God... A place of prayer for all the peoples...”

In fact, Jesus would teach along the Eastern border of the Courtyard of the Gentiles, in a space called, “Solomon’s Portico,” where faithful Jews and nonbelievers alike could listen to his teaching and ask him questions. After his Ascension into heaven, St. Peter and the other Christians continued the tradition of meeting in this sacred space of public dialogue: “Many signs and wonders were done among the people at the hands of the apostles. They were all together in Solomon’s portico” (Acts 5:12).

In explaining the problem contemporary men and women face today, Pope Benedict XVI wrote, “The limit is no longer between those who believe and those who do not believe in God, but between those who want to defend humanity and life, the humanity of each person, and those who want to suffocate humanity through utilitarianism, which could be material or spiritual. Is the border perhaps not between those who recognize the gift of culture and history, of grace and gratuity, and those who found everything on the cult of efficiency, be it scientific or spiritual?” (The Courtyard of the Gentiles, 2013).

The Pope emeritus concluded his remarks on the significance of opening a new Courtyard of the Gentiles with these insights: “The Courtyard of the Gentiles calls for the sharing of a common thirst in a universal, comprehensive, catholic perspective: the opening to each other as [what gives] dynamism to human life.” He called for, “respectful encounters, in sincere dialogue and in a passionate search.”

Come visit the Courtyard of the Gentiles that we have set up online this year. We want to welcome you to our own Solomon’s Portico so you can meet our friends and become one of them.

“A Woman’s Life” Program Note from Richard Danielpour

Dr. Maya Angelou read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed.

Soprano Angela Brown and composer Richard Danielpour at a Nashville dress rehearsal for “A Woman’s Life,” a song cycle composed by Danielpour on the poems of Dr. Maya Angelou. Register for “A Woman’s Life,” an online performance by soprano, Angel Riley, on October 17 at 7:30pm Eastern. Richard Danielpour will be available for a live Q&A session immediately following the concert. Tickets are free, but preregistration is required. Photo by Mitzi Matlock

Full program note from Richard Danielpour:

A WOMAN’S LIFE was composed in the summer of 2008, roughly 2 years after a meeting with Maya Angelou, at her town house in Harlem. I had mentioned to her that the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Symphony were commissioning me to write a work for Angela Brown. Angela had sung the role of Cilla in the Premiere run and in subsequent performances of my opera Margaret Garner. I had an idea of approaching Dr. Angelou, who had been a friend for many years, of a song cycle for a voice and orchestra that would show the trajectory of a woman’s life from childhood, to old age. She mentioned that this already existed, hidden, in her book of collected poems and promptly asked her assistant to furnish her a copy of her book. I was with my wife that afternoon, and she read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed.

Writing the work was relatively straightforward after having memorized the way she read these poems so eloquently and so beautifully. It was not until I finished the score that I realized that I was writing about her life, about the life of Maya Angelou. Now many years later, I understand that it is not only about Dr. Angelou’s life but also about the lives of many women who in their struggles and suffering have managed to prevail.

The Pittsburgh Symphony premiered this 24-minute cycle in October 2009. Subsequent performances by the Philadelphia Orchestra and many other American orchestras have occurred since that time.

Richard Danielpour, October, 2020

An Interview with Angel Riley

Angel Riley is an emerging American soprano embarking on a promising career. Angel’s exciting stage presence and rich vocal color distinguish her performances, resulting in her winning a coveted position as a 2020 Gerdine Young Artist with the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. Register to attend Angel Riley’s October 17 (7:30pm curtain) performance of A Woman’s Life: A Song Cycle by Richard Danielpour on the Poems of Maya Angelou. This concert is free, but requires preregistration.

In the Particular, We Discover the Universal

Angel Riley is an emerging American soprano embarking on a promising career. Angel’s exciting stage presence and rich vocal color distinguish her performances, resulting in her winning a coveted position as a 2020 Gerdine Young Artist with the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. Register to attend Angel Riley’s October 17 (7:30pm curtain) performance of A Woman’s Life: A Song Cycle by Richard Danielpour on the Poems of Maya Angelou. This concert is free, but requires preregistration.

by Meghan Isaacs

On October 17, the Festival of Friendship will present a song cycle by prominent American composer Richard Danielpour, entitled A Woman’s Life, to be performed by soprano Angel Riley, accompanied by Lucy Tucker Yates on piano. The seven-movement work draws on the poetry of Dr. Maya Angelou, and like so much of Dr. Angelou’s oeuvre, presents a very particular experience that manages to resonate universally.

Danielpour set out to compose a song cycle for soprano Angela Brown, and already had Dr. Angelou’s poetry in mind as the libretto when he met with the poet at her townhouse in Harlem. When he asked Angelou if she could provide the text, she immediately knew which poems to select. “I was with my wife that afternoon, and [Dr. Angelou] read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed,” said Danielpour.

Several years after the premiere of A Woman’s Life, emerging young soprano Angel Riley, then a vocal performance student at UCLA, first encountered Danielpour’s music through a performance of his oratorio The Passion of Yeshua, in which she participated with the UCLA chorus. Provoked by his musical language, Riley reached out to Danielpour, who suggested she explore A Woman’s Life. Riley went on to engage in an independent study with Danielpour, during which she (along with Yates as pianist) worked through much of the song cycle under the composer’s guidance. Riley (who recently completed her Master’s degree with aims to begin an artist’s diploma program in fall of 2021) took time to reflect on the music and what it has to say to audiences today.

Tell us about your relationship to A Woman’s Life?

I’ve been with this work for a while now, and I guess the most important thing about this set is that it follows the life of an everyday Black woman in America, and it sheds a positive light on her experience. Richard Danielpour wrote this set for Angela Brown as a thank you gift for performing in his opera Margaret Garner. They both thought it was important to present a work strictly relating to Black women due to the lack of positive portrayals in art and media. This set is so important and unique in that each of the songs comes from a Black woman’s perspective. Dr. Angelou was specifically committed to uplifting Black women in her life. Because of her poetry you see this uplifting of Black women, and Danielpour’s setting of the text really highlights that.

Do you have a favorite song in the cycle, or one you feel you most relate to?

My favorite is the second of the set: “Life Doesn’t Frighten Me.” It’s my favorite, but it’s so difficult for the pianist. I try to capture a young Josephine Baker-type feeling. It talks about all these things — “I’m not afraid of anything; I’m confident; I’m young; There’s nothing you can do to me.”

My other favorite is the very last piece “Many And More.” Specifically, this piece signifies a woman in old age who, although her life did not turn out the way she thought it would, manages to find joy and peace in knowing that there are many men who she’s deserving of but who are not deserving of her. In the fourth movement, she’s confident in her womanhood and sexuality, but feels like she doesn’t need to be bogged down—she can have many men. But by the final piece, she’s gone through love and she’s lost. In the end she found comfort in knowing that she doesn’t necessarily need a man and she can find peace in God. To me, it’s significant: how you can go through life, and your ideas and thoughts about what you want can change. It really signifies wisdom to me.

What was your relationship to the writing of Maya Angelou prior to this performance?

I have always read through her collected poems. I would literally just watch videos of her reciting her poems on YouTube. I’ve often watched her lectures too because she just imparts so much wisdom.

What does this song cycle have to say to our society today?

Just in the way our society is organized, the Black woman is at the bottom. This is a set that intentionally uplifts the Black woman and sheds a positive light on Black women in America. These are beautiful images of a Black woman who has lived, loved, learned, and lost. It is spiritually refreshing and culturally uplifting to Black women in America.

The theme of this festival is “You Will Be Found.” Was does that mean for you? How does this song cycle speak to that?

Although this piece represents Black women, I think the text is so vivid and colorful that everybody can find something in the set that they can relate to. It’s going to make the audience feel something and learn something.

“Do Not Cast Me Off in Time of Old Age”

By Stephen G. Adubato

“‘Do not cast me off in the time of old age; forsake me not when my strength is spent’ (Ps 71:9). This is the plea of the elderly, who fear being forgotten and rejected. Just as God asks us to be his means of hearing the cry of the poor, so too he wants us to hear the cry of the elderly” (Amoris Laetitia 191).

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on and exacerbated the effects of our indifference toward senior citizens, and, in the words of the Pope, have exposed “our vulnerability and uncovered those false and superfluous certainties around which we have constructed our daily schedules, our projects, our habits and priorities...it lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes our people’s souls; all those attempts that anesthetize us with ways of thinking and acting that supposedly ‘save’ us, but instead prove incapable of putting us in touch with our roots and keeping alive the memory of those who have gone before us.”

I myself must admit that I’ve fallen temptation to the cult of “superfluous certainties” and self-affirmation. Especially during my college years, I felt the need to do and acquire “glamorous” things in order to feel like I had value. This anxiety became increasingly sharp around the time I finished college. I was confronted with my waning youth and the dawn of my adulthood.

Around the same time, my grandparents were becoming increasingly sick. They needed me to spend more time taking care of them, and this competed directly with my aspirations of living it up on the weekends.

I remember one weekend I had to give up going to a birthday party so I could stay with them, and while they were napping I started reading the Pope’s latest encyclical, Amoris Laetitia. In it, Francis challenged the postmodern cult of youth and condemned the “throwaway culture” that discards the least productive and most vulnerable in our society, especially the poor, the unborn, and the elderly.

I was challenged by his words. The Pope was proposing that human life has value not just when it’s “useful” or glamorous, but just because it exists. He was also proposing that the fulfillment of our time is not the ideal of efficiency, pleasure, or personal gain, but charity, the gift of self to the point of sacrifice. This flew in the face of the cult of ephemeral pleasure that I had gotten trapped into. I decided to test out the Pope’s proposal through the time I was spending with my grandparents.

I soon started to discover that, although I often got impatient, the time I was spending with them brought out a tenderness and gentleness in me that I didn’t know myself to be capable of. And while it indeed required a sacrifice, I slowly started to find myself more fulfilled by spending my time making a gift of myself than by “living it up.” On top of that, I was learning from my grandparents’ wisdom about my family roots, my culture, and life in general.

Soon after, I decided it would be worthwhile to add more senior day cares to my school’s community service program, which I coordinate. I wanted more students to be able to interact with the elderly. I started searching on Google for centers in Newark, only to find out that many of them had negative reviews complaining of maltreatment and unprofessionalism.

Eventually, I found one center that had very few reviews and a website that hadn’t been updated in quite some time. I took the risk of reaching out, hesitantly, to the owner. She responded enthusiastically, claiming that my email was an answered prayer. She had been looking for opportunities to have young people volunteer with the seniors. After the first week of sending my students there, I was amazed by what I saw happened to them.

Thumbelina Newsome, the director, walks into the center and greets everyone with an overflowing gaze of joy (hence the center’s name. Joy Cometh in the Morning). She approaches each of the seniors, even the grumpiest and most handicapped, as if they were a gift sent to her from above. How does she see such beauty in people who our society tends to write off as useless burdens? Not only this, but she imparted this joy to my students, who initially thought they were going to be stuck working at a “boring community service site with old people.”

I invited Thumbelina to speak about the topic of elder care at an event last year along with Regina Kasun NP, the sister of a dear friend, who works for a geriatric house calls program in Virginia. I invited them to speak once again at this year’s Festival of Friendship, along with my former professor Dr. Charles Camosy, a moral theologian and bioethicist who has written about the Consistent Life Ethic (CLE) and the throwaway culture. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he has written extensively about the dire situations that many senior citizens are facing in nursing homes, challenging the throwaway mentality which allows them to be tossed to the margins of society.

Join us at 6 pm EST on Sunday, October 11th to hear them share their thoughts and experiences. The panel will be followed by a live Q+A session on Hopin.