You Won’t Miss the Burgers

Annunciation (detail), by Matthias Stom

by Suzanne M. Lewis

In 2017, I noticed a sore on my tongue.

By Sunday, October 1, 2017 (the feast of St Thérèse, my Confirmation namesake and special friend), my oral pain was intense as I had the joyful task of thanking each of our speakers and volunteers for their rich contributions and gifts of self throughout that beautiful long weekend at Pittsburgh’s St. Paul Cathedral, where we’d just held our 6th annual Festival of Friendship. I didn’t suspect, then, that two weeks later, on October 15 (Teresa of Avila’s feast), I would call my husband from outside an oncologist’s office to say the three-word sentence that no one wants to speak or hear: “I have cancer.”

In the waiting room before one of my chemo infusions, I met a woman wearing a wide apron, in which she carried her own IV bag that provided a slow drip and allowed her to live at home while receiving treatment. She had arrived for her periodic changing of the bag, and began to explain to me how the medicine she was receiving had changed the flavors of food: “A hamburger just isn’t a hamburger anymore, you know? It tastes funny, like. And forget nachos! I can’t enjoy the taste of my favorite meals. I tell you, if the cancer comes back after this, I’m going to refuse treatment. I’d rather die than live like this.”

This past year, on October 1st, it felt particularly gratifying to kick off the month-long online 2020 Festival of Friendship by offering a panel discussion honoring St. Thérèse and St. Teresa, as well as Edith Stein and Mother Teresa, four “boss” saints who have had such an enormous impact on the world. Only two weeks earlier, my cancer doctors at Cleveland Clinic had pronounced that marvelous and golden word: remission. I knew these four women were at least partly responsible for my healing.

But I’ve also wondered about that woman, whose life meant so little to her that she would trade it for the taste of a Big Mac. Meanwhile, throughout this year, our society’s many failures to respond generously to the exigencies of the pandemic have uncovered a different sort of cancer: despite our stated belief in the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” there are numerous signs that the particular human lives of our fellow citizens do not matter to many of us. This year’s Festival of Friendship addressed this problem from multiple angles, including a focus on the inestimable value of elderly persons; ethical concerns arising from the pandemic; restorative justice in Brazil; and music produced by Black female composers, poets, and vocal artists. These events each revealed a common root cause for the evident disinterest in the lives and well-being of our fellow citizens: a fundamental apathy toward one’s own, unique, God-given life.

At some point, in the experience of each and every authentically religious person, a luminous question arises. This question carries with it all the wonder, all the longing, and all the curious hope expressed in Mary’s query to the angel, “How can this be?” (Lk 1:34). The same astonishment reverberates in Elizabeth’s amazed exclamation, “Who am I that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” (Lk 1:43).

Who am I that You are mindful of me? (cf. Ps 8:4). If you have never asked God some version of this question, then you’ve also never allowed Christ’s own question – Are not all the hairs of your head counted? (cf. Lk 12: 6-7) – to sink down into the roots of your being and startle you out of your petty worldliness. You may engage in all sorts of religious practices, but you haven’t yet embarked on the adventure of a truly religious life. Only after you’ve made a habit of viewing yourself with the esteem God has for you, can you turn your gaze to others and recognize that the Lord cherishes each human life as fiercely and as wholly and as astonishingly as he loves you. Without this intuition, you cannot fulfill Christ’s commandment to love one another as he has loved you.

When you – one lone person – begin to ask this question (“Who am I that You are mindful of me?”), your life becomes something new, something exceptional. Christ refers to this as an “abundant life” (cf. Jn 10:10) or as “the hundredfold here below” (cf. Mt 19:29). With this hundredfold, you develop an endurance you can’t explain and discover a patience you could not produce through force of will. Your creativity grows as you see an increase in your desire to address the predicaments and wounds of others. Soon, another person, unbidden, joins with you. One by one, others see and are magnetically attracted to the two of you. Together you will each roll up your sleeves and take the small, possible steps indicated by the boundless esteem for life you share. You will “start by doing what's necessary, then do what's possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible” (St. Francis of Assisi). Believe me, you will not miss the hamburgers when this happens.

Welcome to your one wild and precious life.

You Will Be Found: The 2020 Festival of Friendship Ushers an Online Revolution of Tenderness

What bread could we possibly share with those far removed from us, or even with those geographically close, whom we cannot visit out of concern for each other’s health and welfare? How could we possibly share a meal with someone who has passed away? The answers to these questions will point us to a way through. We all desperately need to be found. The Festival this year has provided us with the assurance that we will be found... that even you will be found.

By Suzanne M. Lewis

Knowledge is Always an Event. I first heard this phrase in 2009, when it served as the theme for the annual Rimini Meeting of Friendship Among Peoples, a free cultural festival that provides ongoing inspiration for the Festival of Friendship, which is organized by the nonprofit, Revolution of Tenderness. The Festival began in 2012 and has just completed its eighth run. We usually organize this free cultural extravaganza in Pittsburgh, over the course of one rich, packed weekend per year, but in response to 2020’s extraordinary challenges, we made the decision to move all the Festival’s offerings online and to spread them over the course of a month.

Knowledge is Always an Event: Let’s take a look at just one of the words, that final one: event. In our everyday speech, we don’t use the word “event” to mean “unanticipated surprise,” but to understand what the Rimini Meeting’s organizers hoped to communicate with this phrase, we need to invoke the sense of an unplanned, unexpected, unforeseen, impossible to control, exceptional and astonishing breakthrough of something new. Something other. Something we didn’t invite because we didn’t know its address, or even its name. And yet, somewhere in our secret heart, we hoped against hope that this mysterious not-yet-known “something” would arrive and shake us out of our sleepiness. Bring us back to life. Crack us wide open to let the light pour in. Find us.

Thus, inspired by the song from the hit musical, “Dear Evan Hansen, “ we chose You Will Be Found as our theme this year. We decided to bet on our sure hope that the adventure of being surprised by the event of knowledge can and would awaken us to a new, more abundant way to face these difficult times.

Gonxha

For example, during our first panel discussion (October 1st), when Fr. Saldaña revealed that Mother Teresa of Kolkata’s middle name, Gonxha (the saint was christened Agnes Gonxha at her Baptism) means “little flower” in Albanian, I was suddenly struck by the reverberations and the web of communion that suffuses the lives of the four great Teresas, whom we first grouped together simply because of the coincidence that they share a name. Their common name, though, far from being a superficial fact, turns out to be the most significant aspect of their identities… I have called you by name and you are mine. The Mystery summons each of us in this way. And when we address the one who generates us and makes us whole, we beg: hallowed be thy name.

Sir Michael Edwards, during the panel discussion on poetic inspiration, “Deliver My Mouth of the Praise It Owes You,” (October 22), commented on the inexpressibility of God’s name and wondered aloud about why we would ask that this particular aspect, God’s name, be hallowed– rather than God himself? Edwards observed that the more we consider the word “name,” the less we understand its full significance. In fact, earlier in that same talk, Edwards reflected on the “Adamic” language, whose function was to give names to all the animals. Edwards pointed out that the language spoken by Adam and Eve no longer exists; all other human languages can only hint and approximate, but the names that Adam gave to his fellow creatures were capable of expressing each one in its fullness and mystery.

During the second panel discussion to explore our theme, entitled “How Do We Respond to What Finds Us?” Samuel Ewell, III (author of Faith Seeking Conviviality and founder of Eat Make Play, a British charity that fosters conviviality in community life), made reference to a one biblical pun contained in the opening chapters of Genesis: the name “Adam” derives from the Hebrew word אֲדָמָה (“adamah”), meaning "earth.” Thus Adam’s name calls to recognize that we are taken from the earth and have a sacred connection to it. Ewell pointed out that the Hebrew word translated as “tend” or “till” or “cultivate” in Genesis 2: 15 (“The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it”) is שָׁמַר, (“shamar”), which is better translated as: “to observe, to give heed” or “to pay attention to.”

During our final keynote talk, given by Mary Mirrione, she spoke of how following the discipline of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd reveals the urgent and fundamental function of observation in catechesis. Mirrione, who is the National Director of the National Office of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd (CGS), highlighted, in example after delightful example, how a humble and objective attention to the religious life of the child yields extraordinary fruits for our own spiritual journeys and in the lives of children, even those of different nationalities and backgrounds. Mirrione is one of the CGS formation leaders who travels the world to provide formation courses for the Missionaries of Charity, an order founded by Mother Teresa of Kolkata. In the years since Mother Teresa first received the name Gonxha, and later assumed the name Teresa, the order she founded has adopted Catechesis of the Good Shepherd as the only method the Sisters use in their catechetical and educational work around the globe and as an essential part of the formation and education of every novice who enters the order. Her successor explained the reason for this choice: “In the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, we find true contemplation.”

In Every Separation is a Link: Being Found Behind Bars, one panelist, Lance Graham, spoke about enrolling in a creative writing class, offered through Arizona State University, while he was a prisoner at the Arizona Department of Corrections. The process of writing and of receiving feedback and companionship through the class, “found” Graham in an extraordinary way. Once out of prison, he completed advanced studies and became an instructor in the same ASU program he’d enrolled in. To describe his own journey, Graham quoted Tupac Shakur: “Did you hear of the rose that grew from a crack in the concrete?” The very next evening, before the screening of the new opera, “Sweet Land,” Lucy Tucker Yates (who played in the opera’s orchestra and whose son, Leander Rajan, sang the part of Speck in the opera), described an outtake from the opera: as a train passes by, its plume of exhaust leaves behind a trail of white flowers, which Speck then picks, one by one. Yates explained that the train smoke represents our prayers (as does incense during a Vespers service), so the small flowers embody our cry for companionship, for wholeness, for healing of the earth, and for true dialogue between and among peoples. One member of our audience recalled attending the Festival’s opening event and observed, “Listening to Francesca tell the story of the Little Flower, it really struck me for the first time that we are found even in our littleness.”

The littlest flowers, first made to bloom in the garden of Eden – where the earth-man Adam was given the sacred duty to contemplate them and the privilege to name them – these little flowers have found their expression in the hints and signs we glean from the lives of our four holy Teresas, who through some strange new math, together embody an equation that might be expressed like this: 1+1+1+1=(10)^(10^100)4 (one plus one plus one plus one equals googolplex to the power of four). Tennessee Williams, in Camino Real, wrote: “The flowers in the mountains have broken the rocks.” Indeed, and what more obdurate stone is there to be found that could compare to the hardness of the human heart?

One Multitudinous Human Voice

Out of the numerous musical performances we offered over the course of the month, there are three worth highlighting as examples of the sheer diversity of styles, performers, and composers we witnessed this October: Jazz is Love, a concert of Mary Lou Williams’ compositions performed by the Deanna Witkowsky Trio; soprano Angel Riley’s performance of A Woman’s Life: A Song Cycle by Richard Danielpour on seven poems by Maya Angelou; and To Live in a Sea of Happiness, a concert of traditional samba music from Rio de Janeiro, performed and introduced by Ney Vasconcelos and Antonio Gomes from their local haunts in Brazil.

Deanna Witkowski first discovered the music of Mary Lou Williams, a Black composer originally from Pittsburgh, 19 years ago. Deanna describes the moment: “She Composes a Jazz Mass: reading this headline changed my own career trajectory. That was the year that Dr. Billie Taylor invited me to perform at the Kennedy Center’s Mary Lou Williams Festival. Now, I didn’t know much, at the time, about Mary Lou Williams’ music… So I visited the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers, where her archives are held, and there I read this headline… I had written two of my own jazz masses. Now, with Mary Lou as my mentor, I began to book my trio in churches around the country, doing my own sacred music.” While inviting friends to listen to Deanna’s concert, which took place on October 4, I would describe Mary Lou as the greatest of the Jazz Greats you have never heard of. Her career spanned a many of jazz’s subgenres and movements of the twentieth century, and she collaborated with and mentored figures such as Jelly Roll Morton, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Cab Calloway, Bud Powell, Theolonius Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie, to name a few. As a jazz pianist, composer, and arranger, Mary Lou received the highest respect from the towering figures of jazz in her day, but her name and memory have been largely obscured to history. One of our hopes, in inviting Deanna to give this concert, was to lift that veil of obscurity for our friends. While working to reveal Mary Lou’s opus for new generations of audiophiles, Deanna described how Mary Lou and her music found her, as a pianist, a composer, and in her spiritual life. How striking it was when Deanna remarked that the most important quality for a jazz musician is the capacity to observe and to listen! Without this close and intense concentration on the other musicians in one’s band, the vital heart of jazz’s special contribution to the world of music would be lost. Each performer must give the full force of her attention to her fellow musicians in order to engage in a meaning-filled and lyrical “dialogue” or conversation amongst the various improvisations born from the encounter with this living, present-tense music. The imperative to pay attention recalled the insight that when God invites Adam to cultivate the garden, scripture uses the word שָׁמַר, (“shamar”), that is, “to heed or to observe,” and which evokes how we learned from Mary Mirrione how crucial it is for catechists to commit themselves to observation.

In A Woman’s Life, the Festival of Friendship concert given on October 17, we listened to a different Black female musician, Angel Riley, accompanied by Lucy Yates on piano, sing the song cycle composed by Richard Danielpour on Maya Angelou’s poems. Angel’s and Mary Lou’s lives, musical commitments, training, and performance histories could not appear to be more different, yet each of these women gives expression to a unique cultural presence that has endured suffocating and brutal campaigns to repress and silence it: the Black woman’s experience in American life. Angel explained, during an interview with Meghan Isaacs, that it is “[...] important to present a work strictly relating to Black women due to the lack of positive portrayals in art and media. This set is ... unique in that each of the songs comes from a Black woman’s perspective. Dr. Angelou was specifically committed to uplifting Black women in her life.” Angel pointed out that Angelou’s poetry shows “this uplifting of Black women, and Danielpour’s setting of the text really highlights that.” Richard Danielpour recalls, in the program note that he wrote for the Festival’s concert, that he approached “Dr. Angelou, who had been a friend for many years, [for help in composing] a song cycle for a voice and orchestra that would show the trajectory of a woman’s life from childhood, to old age. She mentioned that this already existed, hidden, in her book of collected poems and promptly asked her assistant to furnish her a copy of her book. [... That day,] she read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed.” Among Danielpour’s many extraordinary gifts, he has a most striking capacity to attend to and map the topography and texture of performers’ unique instrumental landforms and waterways, interior distances, geological formations, microclimates, and botanical riches... and to then compose music that both fits and is complementary to these human, musical landscapes. So that day in Dr. Angelou’s home, he soaked in every nuance of her compelling performance and later remembered the exact timbre and every cadence in her reading. These elements informed and gave life to the music he later composed for the poems. Each time during the Festival that a new speaker or performer returned to this theme of attention and observation, new understandings and directions opened up for those of us who were privileged to be present.

After the concert, given by Soprano Angel Riley, accompanied on piano by Lucy Tucker Yates, the world-renowned composer of “A Woman’s Life,” Richard Danielpour, joined the live Q&A session with the audience and the performers. He expressed his wonder at the name of the nonprofit that sponsors the Festival of Friendship: Revolution of Tenderness and related how he counsels all his students, “If you want to be an artist, you need two qualities; you need both curiosity and generosity. And when you combine these two qualities, you get tenderness.” He went on to explain how important tenderness is for the creative process. The next day, he reached out to Revolution of Tenderness to explore the possibility of collaborating on a project that he’d been thinking about for some time: the performance of a new composition that will promote healing for our world as it suffers the effects of Covid-19 and the particularly divisive 2020 election season. As a result of this invitation, I’m very excited to announce that Revolution of Tenderness has commissioned and will debut a new piece for string instruments, entitled “Homeward.” We will release this performance sometime early in 2021.

The samba concert video, To Live in a Sea of Happiness, seems, at first blush, to take us far, far away from the desires and the impetus that gave rise to the other two concerts. Suddenly, on October 23, we found ourselves in Brazil, with some new friends, who wanted to share a musical tradition belonging to the favelas, or slums, of Rio de Janeiro. Samba de raiz (“roots samba”) expresses a strange joy and sensitivity to beauty in the face of poverty, heartbreak, exclusion, toilsome labor, and even death. “Each inhabitant of the favela bears an individual face marked by her own distinct pain. The fierce fight favelados must conquer in order to endure every minute of life, with its myriad adversities, has made each of them a maestro in the art of survival. The samba musician of the favela does not hide this acquired skill, but rather, through poetry and music, expresses and generously shares it with the world.[1]” The beautiful video, filmed and produced by Marcelo Rocha, performed by Ney Vasconcelos (on guitar), narrated by Antonio (Toninho) Gomez (who also provided the vocals), and featuring a cameo by flutist Alessandra Sterzi, called forth a powerful impression: that these far-flung friends had invited us to join a living adventure of musical companionship through a land both new and familiar: the experience of the human condition, lived with great intensity.

The instruments were different in each of the three concerts; the performers sang in different languages; in each case, the personal histories of composers and musicians seemed to have very little in common; and the ambient sights and sounds all gave rise to diverse contextual atmospheres. Yet, surveying all three concerts, a unity emerges, despite the differences in genres, musical traditions, and cultural contexts. In each case, we heard the expression of a single human Voice – one that takes form in a dizzying collection of accents, dialects, tones, vibrations, and volumes – but one Voice, nonetheless, that somehow manages to sing the rest of us listeners into a greater awareness of and appreciation for our own humanity.

Shared Bread

Following the definition of the word “event” that we began with, we can readily see how 2020 has struck us as wholly unanticipated, unforeseen, unintended, unplanned, and impossible to control; but the year’s surprises have also been unwanted, constricting, and paralyzing. Bewildered by an unprecedented death toll, disease, hatred, violence, and financial and emotional hardships, we have grieved and raged against the limits our new circumstances have imposed. We long for a return to “normal,” even as we know, in our bones, that this return is impossible.

In the midst of this set of challenges, my friends and I dared to imagine that we could be “found.” In fact, our conviction has been so strong on this point, that we had the nerve to say to the world, You Will Be Found, and to invite new friendships to develop on the basis of this one judgment: that even here, in 2020, and without denying a single occasion for human suffering that arose in this year, the event of knowledge can awaken us to the hidden light that pervades even the deepest darkness.

The insights gleaned from our many panel discussions – especially the ones that addressed the problems that plague our culture now: a lack of consensus concerning public health policy, how to find the most ethical way to live the limits imposed by the virus, how to uphold the dignity of each and every human life, etc. – uncovered many unusual and surprising answers: the experience of prisoners can inform and enrich our own need for redemption and freedom; literature and fine arts can become means to respond to (and find responses to) pain and joy, weakness and strength, loss and love; and our need for companions can somehow, miraculously, find an answer that cannot be halted though oceans separate us, technology frustrates and seems to alienate us, and culture and language seem to throw up barriers to understanding. Even disease and death do not have the final word, as we learned from our exploration into the lives of saints and other “revolutionaries of tenderness,” such as our buddies who share the name Teresa or our new pals, Charles de Foucauld and Mary Lou Williams, whom we met through Deanna. This point is the most exceptional of all. Because the root meaning of the word “companion,” is “one who breaks bread with another” (from Latin com "with, together" + panis "bread," from PIE root *pa- "to feed"). What bread could we possibly share with those far removed from us, or even with those geographically close, whom we cannot visit out of concern for each other’s health and welfare? How could we possibly share a meal with someone who has passed away? The answers to these questions will point us to a way through. We all desperately need to be found. The Festival this year has provided us with the assurance that we will be found... that even you will be found.

Suzanne M. Lewis is the Founder and Coordinator of Revolution of Tenderness, the nonprofit that organizes the Festival of Friendship and several other initiatives, including an arts magazine called Convivium Journal, a small publishing house, a radio station, a podcast, and various educational programs and classes. Suzanne earned Masters’ degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Bryn Mawr School of Social Services. She has published several books of prayer and is the mother of five daughters.

The theme for the 2021 Festival will be: Your One Wild and Precious Life.

[1] Pier Luigi Bernareggi, Rosa Brambilla, UM CÉU NO CHÃO. A SKY ON EARTH. THE MORRO SAMBA, from the Rimini Meeting website.

Your One Wild and Precious Life

Join us on this adventure. Share your ideas, your help, your ardent prayers, your particular talents, your resources, and your energy as together we prepare our 9th annual Festival of Friendship. Your one wild and precious life cannot be substituted or duplicated.

Photo courtesy of: Sister Thea Bowman Cause for Canonization

We are overjoyed to announce the theme for Festival of Friendship 2021: Your One Wild and Precious Life.

You meet certain people along the path of life: people who seem more alive, more human, more original. They stop you in your tracks. They make you ask yourself: What is the secret to their fascination? How did they find their intensity? Where can I pick some of that up for myself?

Sister Thea Bowman is one of those people. Next year, we’ll examine her life for clues to the source of her ardor and joy. If we want to fully inhabit our lives as Sister Thea did, we need the courage to stop wasting our own time, and to mean something luminous, grand, wild, exceptional, and precious when we use the word “I.”

Join us on this adventure. Share your ideas, your help, your prayers, your particular talents, your resources, and your energy as together we prepare our 9th annual Festival of Friendship. Your one wild and precious life cannot be substituted or duplicated. St. Catherine of Sienna wrote, be who you were meant to be, and you will set the world on fire. Let’s create a conflagration together!

Contact me at suzanne [@] revolutionoftenderness [dot] net in order to join the Revolution of Tenderness!

The Festival of Friendship as a Courtyard of the Gentiles

“The Courtyard of the Gentiles calls for the sharing of a common thirst in a universal, comprehensive, catholic perspective: the opening to each other as [what gives] dynamism to human life.” He called for, “respectful encounters, in sincere dialogue and in a passionate search.”

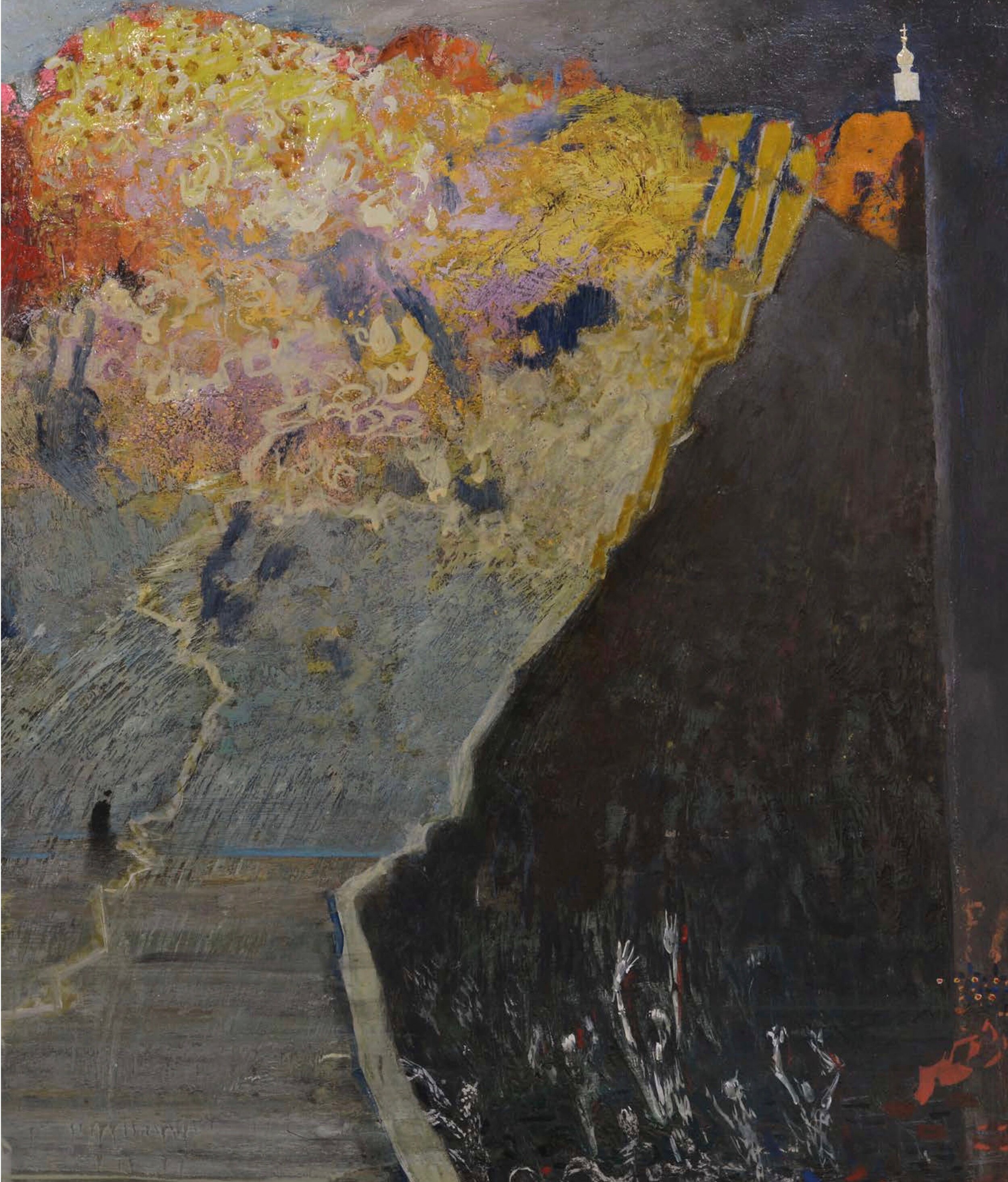

Road to the Temple, by Victor Zaretsky

In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced a new project, very dear to his heart, called the “Courtyard of the Gentiles.” His desire was to open a space for dialogue among peoples of different faiths or no faith. He described the modern world as "a windowless building of cement, in which man controls the temperature and the light; and yet, even in a self-constructed world, we draw upon the 'resources' of God, which we then transform into our own products. What can we say then? It is necessary to reopen the windows, to see again the vastness of the world, of heaven and earth, and to learn to use all things in a good way." This statement expresses our own vision at Revolution of Tenderness. Taking St. Paul's motto, "Test everything; keep what is good" as our own, we seek to reopen the windows Pope Benedict spoke of. Now, more than ever before, this is an urgent undertaking.

Pope Benedict XVI took, as his inspiration for the initiative, the name for the open air atrium at the Temple of Jerusalem, “a space in which everyone could enter, Jews and non-Jews, …[to engage] in a respectful and compassionate exchange. This was the Court of the Gentiles… a space that everyone could traverse and could remain in, regardless of culture, language or religious profession. It was a place of meeting and of diversity.” Our various initiatives, especially the Festival of Friendship, seek to provide similar spaces where “respectful and compassionate exchange” can happen.

Pope Benedict reminded us that Jesus said, “The Temple must be a house of prayer for all the nations (Mk 11: 17). Jesus was thinking of the ‘Court of the Gentiles,’ which he cleared of extraneous affairs so that it could be a free space for the Gentiles who wished to pray there to the one God... A place of prayer for all the peoples...”

In fact, Jesus would teach along the Eastern border of the Courtyard of the Gentiles, in a space called, “Solomon’s Portico,” where faithful Jews and nonbelievers alike could listen to his teaching and ask him questions. After his Ascension into heaven, St. Peter and the other Christians continued the tradition of meeting in this sacred space of public dialogue: “Many signs and wonders were done among the people at the hands of the apostles. They were all together in Solomon’s portico” (Acts 5:12).

In explaining the problem contemporary men and women face today, Pope Benedict XVI wrote, “The limit is no longer between those who believe and those who do not believe in God, but between those who want to defend humanity and life, the humanity of each person, and those who want to suffocate humanity through utilitarianism, which could be material or spiritual. Is the border perhaps not between those who recognize the gift of culture and history, of grace and gratuity, and those who found everything on the cult of efficiency, be it scientific or spiritual?” (The Courtyard of the Gentiles, 2013).

The Pope emeritus concluded his remarks on the significance of opening a new Courtyard of the Gentiles with these insights: “The Courtyard of the Gentiles calls for the sharing of a common thirst in a universal, comprehensive, catholic perspective: the opening to each other as [what gives] dynamism to human life.” He called for, “respectful encounters, in sincere dialogue and in a passionate search.”

Come visit the Courtyard of the Gentiles that we have set up online this year. We want to welcome you to our own Solomon’s Portico so you can meet our friends and become one of them.

“A Woman’s Life” Program Note from Richard Danielpour

Dr. Maya Angelou read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed.

Soprano Angela Brown and composer Richard Danielpour at a Nashville dress rehearsal for “A Woman’s Life,” a song cycle composed by Danielpour on the poems of Dr. Maya Angelou. Register for “A Woman’s Life,” an online performance by soprano, Angel Riley, on October 17 at 7:30pm Eastern. Richard Danielpour will be available for a live Q&A session immediately following the concert. Tickets are free, but preregistration is required. Photo by Mitzi Matlock

Full program note from Richard Danielpour:

A WOMAN’S LIFE was composed in the summer of 2008, roughly 2 years after a meeting with Maya Angelou, at her town house in Harlem. I had mentioned to her that the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Symphony were commissioning me to write a work for Angela Brown. Angela had sung the role of Cilla in the Premiere run and in subsequent performances of my opera Margaret Garner. I had an idea of approaching Dr. Angelou, who had been a friend for many years, of a song cycle for a voice and orchestra that would show the trajectory of a woman’s life from childhood, to old age. She mentioned that this already existed, hidden, in her book of collected poems and promptly asked her assistant to furnish her a copy of her book. I was with my wife that afternoon, and she read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed.

Writing the work was relatively straightforward after having memorized the way she read these poems so eloquently and so beautifully. It was not until I finished the score that I realized that I was writing about her life, about the life of Maya Angelou. Now many years later, I understand that it is not only about Dr. Angelou’s life but also about the lives of many women who in their struggles and suffering have managed to prevail.

The Pittsburgh Symphony premiered this 24-minute cycle in October 2009. Subsequent performances by the Philadelphia Orchestra and many other American orchestras have occurred since that time.

Richard Danielpour, October, 2020

An Interview with Angel Riley

Angel Riley is an emerging American soprano embarking on a promising career. Angel’s exciting stage presence and rich vocal color distinguish her performances, resulting in her winning a coveted position as a 2020 Gerdine Young Artist with the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. Register to attend Angel Riley’s October 17 (7:30pm curtain) performance of A Woman’s Life: A Song Cycle by Richard Danielpour on the Poems of Maya Angelou. This concert is free, but requires preregistration.

In the Particular, We Discover the Universal

Angel Riley is an emerging American soprano embarking on a promising career. Angel’s exciting stage presence and rich vocal color distinguish her performances, resulting in her winning a coveted position as a 2020 Gerdine Young Artist with the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. Register to attend Angel Riley’s October 17 (7:30pm curtain) performance of A Woman’s Life: A Song Cycle by Richard Danielpour on the Poems of Maya Angelou. This concert is free, but requires preregistration.

by Meghan Isaacs

On October 17, the Festival of Friendship will present a song cycle by prominent American composer Richard Danielpour, entitled A Woman’s Life, to be performed by soprano Angel Riley, accompanied by Lucy Tucker Yates on piano. The seven-movement work draws on the poetry of Dr. Maya Angelou, and like so much of Dr. Angelou’s oeuvre, presents a very particular experience that manages to resonate universally.

Danielpour set out to compose a song cycle for soprano Angela Brown, and already had Dr. Angelou’s poetry in mind as the libretto when he met with the poet at her townhouse in Harlem. When he asked Angelou if she could provide the text, she immediately knew which poems to select. “I was with my wife that afternoon, and [Dr. Angelou] read seven poems to us, sometimes clapping in rhythm with the poems, sometimes repeating lines of the poem that were not actually repeated in the text. By the time she finished, I was in tears. It was one of the greatest performances in my life that I had ever witnessed,” said Danielpour.

Several years after the premiere of A Woman’s Life, emerging young soprano Angel Riley, then a vocal performance student at UCLA, first encountered Danielpour’s music through a performance of his oratorio The Passion of Yeshua, in which she participated with the UCLA chorus. Provoked by his musical language, Riley reached out to Danielpour, who suggested she explore A Woman’s Life. Riley went on to engage in an independent study with Danielpour, during which she (along with Yates as pianist) worked through much of the song cycle under the composer’s guidance. Riley (who recently completed her Master’s degree with aims to begin an artist’s diploma program in fall of 2021) took time to reflect on the music and what it has to say to audiences today.

Tell us about your relationship to A Woman’s Life?

I’ve been with this work for a while now, and I guess the most important thing about this set is that it follows the life of an everyday Black woman in America, and it sheds a positive light on her experience. Richard Danielpour wrote this set for Angela Brown as a thank you gift for performing in his opera Margaret Garner. They both thought it was important to present a work strictly relating to Black women due to the lack of positive portrayals in art and media. This set is so important and unique in that each of the songs comes from a Black woman’s perspective. Dr. Angelou was specifically committed to uplifting Black women in her life. Because of her poetry you see this uplifting of Black women, and Danielpour’s setting of the text really highlights that.

Do you have a favorite song in the cycle, or one you feel you most relate to?

My favorite is the second of the set: “Life Doesn’t Frighten Me.” It’s my favorite, but it’s so difficult for the pianist. I try to capture a young Josephine Baker-type feeling. It talks about all these things — “I’m not afraid of anything; I’m confident; I’m young; There’s nothing you can do to me.”

My other favorite is the very last piece “Many And More.” Specifically, this piece signifies a woman in old age who, although her life did not turn out the way she thought it would, manages to find joy and peace in knowing that there are many men who she’s deserving of but who are not deserving of her. In the fourth movement, she’s confident in her womanhood and sexuality, but feels like she doesn’t need to be bogged down—she can have many men. But by the final piece, she’s gone through love and she’s lost. In the end she found comfort in knowing that she doesn’t necessarily need a man and she can find peace in God. To me, it’s significant: how you can go through life, and your ideas and thoughts about what you want can change. It really signifies wisdom to me.

What was your relationship to the writing of Maya Angelou prior to this performance?

I have always read through her collected poems. I would literally just watch videos of her reciting her poems on YouTube. I’ve often watched her lectures too because she just imparts so much wisdom.

What does this song cycle have to say to our society today?

Just in the way our society is organized, the Black woman is at the bottom. This is a set that intentionally uplifts the Black woman and sheds a positive light on Black women in America. These are beautiful images of a Black woman who has lived, loved, learned, and lost. It is spiritually refreshing and culturally uplifting to Black women in America.

The theme of this festival is “You Will Be Found.” Was does that mean for you? How does this song cycle speak to that?

Although this piece represents Black women, I think the text is so vivid and colorful that everybody can find something in the set that they can relate to. It’s going to make the audience feel something and learn something.

“Do Not Cast Me Off in Time of Old Age”

By Stephen G. Adubato

“‘Do not cast me off in the time of old age; forsake me not when my strength is spent’ (Ps 71:9). This is the plea of the elderly, who fear being forgotten and rejected. Just as God asks us to be his means of hearing the cry of the poor, so too he wants us to hear the cry of the elderly” (Amoris Laetitia 191).

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on and exacerbated the effects of our indifference toward senior citizens, and, in the words of the Pope, have exposed “our vulnerability and uncovered those false and superfluous certainties around which we have constructed our daily schedules, our projects, our habits and priorities...it lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes our people’s souls; all those attempts that anesthetize us with ways of thinking and acting that supposedly ‘save’ us, but instead prove incapable of putting us in touch with our roots and keeping alive the memory of those who have gone before us.”

I myself must admit that I’ve fallen temptation to the cult of “superfluous certainties” and self-affirmation. Especially during my college years, I felt the need to do and acquire “glamorous” things in order to feel like I had value. This anxiety became increasingly sharp around the time I finished college. I was confronted with my waning youth and the dawn of my adulthood.

Around the same time, my grandparents were becoming increasingly sick. They needed me to spend more time taking care of them, and this competed directly with my aspirations of living it up on the weekends.

I remember one weekend I had to give up going to a birthday party so I could stay with them, and while they were napping I started reading the Pope’s latest encyclical, Amoris Laetitia. In it, Francis challenged the postmodern cult of youth and condemned the “throwaway culture” that discards the least productive and most vulnerable in our society, especially the poor, the unborn, and the elderly.

I was challenged by his words. The Pope was proposing that human life has value not just when it’s “useful” or glamorous, but just because it exists. He was also proposing that the fulfillment of our time is not the ideal of efficiency, pleasure, or personal gain, but charity, the gift of self to the point of sacrifice. This flew in the face of the cult of ephemeral pleasure that I had gotten trapped into. I decided to test out the Pope’s proposal through the time I was spending with my grandparents.

I soon started to discover that, although I often got impatient, the time I was spending with them brought out a tenderness and gentleness in me that I didn’t know myself to be capable of. And while it indeed required a sacrifice, I slowly started to find myself more fulfilled by spending my time making a gift of myself than by “living it up.” On top of that, I was learning from my grandparents’ wisdom about my family roots, my culture, and life in general.

Soon after, I decided it would be worthwhile to add more senior day cares to my school’s community service program, which I coordinate. I wanted more students to be able to interact with the elderly. I started searching on Google for centers in Newark, only to find out that many of them had negative reviews complaining of maltreatment and unprofessionalism.

Eventually, I found one center that had very few reviews and a website that hadn’t been updated in quite some time. I took the risk of reaching out, hesitantly, to the owner. She responded enthusiastically, claiming that my email was an answered prayer. She had been looking for opportunities to have young people volunteer with the seniors. After the first week of sending my students there, I was amazed by what I saw happened to them.

Thumbelina Newsome, the director, walks into the center and greets everyone with an overflowing gaze of joy (hence the center’s name. Joy Cometh in the Morning). She approaches each of the seniors, even the grumpiest and most handicapped, as if they were a gift sent to her from above. How does she see such beauty in people who our society tends to write off as useless burdens? Not only this, but she imparted this joy to my students, who initially thought they were going to be stuck working at a “boring community service site with old people.”

I invited Thumbelina to speak about the topic of elder care at an event last year along with Regina Kasun NP, the sister of a dear friend, who works for a geriatric house calls program in Virginia. I invited them to speak once again at this year’s Festival of Friendship, along with my former professor Dr. Charles Camosy, a moral theologian and bioethicist who has written about the Consistent Life Ethic (CLE) and the throwaway culture. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he has written extensively about the dire situations that many senior citizens are facing in nursing homes, challenging the throwaway mentality which allows them to be tossed to the margins of society.

Join us at 6 pm EST on Sunday, October 11th to hear them share their thoughts and experiences. The panel will be followed by a live Q+A session on Hopin.

Spanish Soul: The Legacy of Graciano Tarragó

Soprano Camille Zamora

By Camille Zamora

Camille Zamora's performance of these Spanish art songs, from her album, If the Night Grows Dark, will be presented on Saturday, October 3, 2020 at 7:30pm. This online presentation will be offered at no cost, but registration is required. To sign up, please see the Revolution of Tenderness homepage at www.revolutionoftenderness.net

Music informs identity. The little tune that floats into an open window from the street below, the lullaby that vibrates in a low hum from a nearby room, the half-remembered refrain of a long-ago love song — these souvenirs in sound tell us where we’re from and where we’re going. And in sharing our songs of joy, sorrow, passion, and peace, we reconnect with ourselves and each other, and rediscover who we really are.

Composers have long taken inspiration from homegrown tunes. Classical standard-bearers from Haydn to Beethoven crafted countless arrangements of folksongs, and the Romantics who followed — Brahms, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Franck, Saint-Saëns — breathed new life into symphonic forms through their use of regional song. In folksong, they discovered the sinuous, singable melodies and bracing rhythms that refreshed their concert halls like so many country breezes.

During the first decades of the 20th century, composers intensified what Australian composer/arranger Percy Grainger called their “folk-fishing trips.” (Grainger himself had traveled the back roads of the British isles in 1905, early phonograph in hand, recording elderly villagers in nearly forgotten ballads, shanties, and lullabies.) As industrialization and urban migration continued to erode rural identity, more composers began to tap their musical roots and notate what previously had been a purely oral tradition of cradle, campfire, and countryside.

Composers including Dvořák, Holst, Vaughan Williams, Britten, Bartók, and Kodály ushered in a nationalist music movement that sought to preserve what totalitarian regimes were threatening. Later, the use of regional song in the work of Hindemith, Lutoslawski, Górecki, and others became a deeply personal way to assert identity and register protest. These local musical expressions would blossom in the “Singing Revolutions” of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, contributing to the end of Soviet rule.

Graciano Tarragó (1892–1973) was among the 20th century composers who mined their countries’ musical gold, in his case against the backdrop of Franco’s Spain. A teacher, composer, arranger, and performer, Tarragó was part of the lineage of Catalonian guitar maestros — from Fernando Sor to Francisco Tárrega to his own teacher, Miguel Llobet — whose contributions elevated the guitar from humble “tavern accompanist” to serious solo instrument deserving of dedicated study and nuanced composition.

Tarragó’s studio at Barcelona’s Conservatori del Liceu nurtured a generation of Spanish musicians that included his daughter, the virtuosa Renata Tarragó, and the young soprano Victoria de los Angeles. Working within the Late Romantic aesthetic of his youth, he delved into Spain’s two particular motherlodes: its early music treasury and its rich folk tradition. From these complementary veins, he forged an inimitable Spanish voice.

For Tarragó, who played Renaissance vihuela in addition to guitar, early music was an artistic touchstone. The musicologist Felip Pedrell had recently recovered the compositions of Renaissance master Tomás Luis de Victoria (“the Spanish Palestrina”) and his contemporaries, offering new clues to the origins of Spanish musical identity. The perfectly balanced contrapuntal and harmonic elements of this early repertoire spoke to Tarragó’s direct style and honed technique. In arranging these works, he found a purity of musical structure that demanded utmost tonal clarity and focus. Like Bach’s arias, Tarragó’s arrangements of these pieces locate their magic, as well as their difficulty, in their deceptive simplicity.

By contrast, Tarragó’s folksong arrangements offer the fiery, extroverted elements typically associated with Spanish sound: driving dance rhythms, exotic flamenco scales reminiscent of their Arab origins, and impassioned, quasi-improvisatory flourishes. Many of these songs are colored by flamenco cante jondo (literally “deep singing”), with arching melismatic phrases that soar and plunge to express tenderness, longing, and desire. In these works, we hear what the composer Isaac Albéniz referred to as the essence “of the people, our Spanish people… color, sunlight, flavor of olives… like the carvings in the Alhambra, those peculiar arabesques that say nothing with their turns and shapes, but which are like the air, like the sun, like the blackbirds, like the nightingales in the gardens…”

My own journey with Tarragó began on a hot afternoon in Madrid when, taking refuge from the midday sun in a dusty music shop on a side street, I stumbled across some out-of-print folios. My Texan-Spanish-New-Yorker self recognized in the yellowed pages certain essential parts of my own musical makeup: the canciones my father sang to me as a child, the stories of my grandfather serenading my grandmother, and my very first classical album featuring Victoria de los Angeles singing zarzuela in her crystalline soprano. (The fact that her family hailed from the town of Zamora allowed me to imagine her as my angelic distant cousin.)

Flipping through those old scores that afternoon and humming under my breath, I fell in love with the songs. I could hear the light-dark Spanish sensibility built into the melodies as into the chiaroscuro of my voice — the quicksilver vacillations between major and minor, the deep shadows even in the brightest noon, the cocina counterpoint of comfort and spice, the awareness of sorrow in joy and joy in sorrow.

I bought all the collections I could get my hands on that day, and in the weeks that followed, I read through song after song, noticing one arranger’s name in particular: Graciano Tarragó. It was not a name I had heard before. Tarragó was virtually unmentioned in music history books, but I was struck by his gentle genius. Each song seemed an opera in miniature, a tiny window on a vast world of emotion, identity, and story-telling. These were songs infused with duende, the heightened emotional/spiritual connection that exists in a realm beyond technique — what could be loosely translated as “soul.”

In Tarragó’s setting of the 16th century song “Si la noche se hace oscura” (“If the night grows dark”), we hear a woman’s soul. In her exposed opening phrases, she calls out to her love. The night is dark and the road is short, so why does he not come to her? She pours all of her vulnerability, tenderness, and desire into a melodic arc that rises and falls as inexorably as nightfall itself. It is a song of heartache and withdrawal. It is also a song of the quiet joy of choosing to love completely, with abandon, even in the face of separation and uncertainty. Delivered by Tarragó across centuries to this moment, to a world suddenly defined by lockdown and distancing, it feels like a gift.

Music can be a delivery system for shared hope, for individual passion, for ancestral coding, for peace. A simple song can allow us to send our voice, our breath, out across the night air, over hills and highways, to curl around our beloved in the darkness. Through song, Tarragó seems to say, we honor our teachers, our heritage, our hearts. Through song, we are restored to the people and places we love; we are restored, ultimately, to ourselves. Aun si la noche se hace oscura. Even if the night grows dark.